umbra.

Exposición individual

Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira

2025

umbra.

[...] En umbra. Manuel Minch establece un diálogo con el patrimonio natural y cultural de Altamira, abordado desde una perspectiva sensorial y cognitiva. En su propuesta, se enfoca en el reconocimiento y cuestionamiento de la arqueología, así como en el carácter clasificatorio inherente al pensamiento científico. En lugar de desenterrar, identificar y asignar un significado, Minch opta por enterrar, velar y sellar. De esta forma, su trabajo escapa a las categorías rígidas o previamente aprobadas, invitando al espectador a una experiencia más libre, tanto en el acto de observar como en el de intuir. Así, la capacidad de identificar los elementos presentados de manera velada y translúcida se convierte en una experiencia propia del espectador. Los objetos, atrapados en esa zona más oscura de la sombra —la umbra— permanecen sellados, sin ser revelados por completo. No se les otorga un significado predefinido ni un conocimiento adicional; en cambio, se establece una comunicación directa entre el objeto y el espectador, entre la experiencia de observar y el proceso de descubrir formas, texturas, fragmentos minerales y restos vegetales del entorno de Altamira, mediada por la mirada y el gesto artístico de Manuel Minch.

Pilar Fatás y Sofía Cuadrado

Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira

Fajanas

In umbra. Manuel Minch establishes a dialogue with the natural and cultural heritage of Altamira, approached from a sensory and cognitive perspective. His proposal focuses on the recognition and questioning of archaeology, as well as on the classificatory nature inherent to scientific thought. Rather than unearthing, identifying, and assigning meaning, Minch chooses to bury, veil, and seal. In doing so, his work escapes rigid or pre-approved categories, inviting the viewer into a freer experience—both in the act of observing and in that of intuiting.

Thus, the ability to identify the elements presented in a veiled and translucent manner becomes an experience unique to each viewer. The objects, trapped within that darker zone of shadow—the umbra—remain sealed, never fully revealed. They are not granted predefined meaning or additional knowledge; instead, a direct communication is established between object and observer, between the experience of looking and the process of discovering forms, textures, mineral fragments, and vegetal remains from the surroundings of Altamira—mediated through the gaze and artistic gesture of Manuel Minch.

Pilar Fatás and Sofía Cuadrado

National Museum and Research Center of Altamira

Imaginen un objeto cualquiera, uno que no reconocen, un material cualquiera contenido en una forma que se resiste a ser definida. Hasta que no lo nombren ese objeto no es nada, apenas existe. Imaginen otro objeto a una distancia prudencial del anterior, otra forma, otra materia, otra masa cualquiera. Hasta que no la nombren, no existe ninguna relación entre ambos. ¿Quién, entre todos los observadores anónimos y mudos, posee la prerrogativa de darle un nombre a aquello que aún no lo tiene? Todos y ninguno, puesto que poner nombres a las cosas es una tarea paradójicamente anónima. Todo nombre es, además, fruto de un desarrollo histórico. Eso sí: cuanto más lejano, menos rastreable, como una huella que se borra con el tiempo.

Imaginen ahora que ambos objetos existen, que tienen nombre, que se ha llegado a un acuerdo para dárselo, que ese acuerdo es convencional, de todos y de ninguno, y que sobrevive inmutable a las estaciones del año, a los años, a las edades y a las eras. Ambos objetos y la relación que han establecido tienen, por fin, un significado que puede ser transmitido, matizado, discutido y, finalmente, rechazado. En pocas palabras, existe, por fin, conocimiento: el objeto ya no está mudo, ya no está solo, ahora convive con multitud de formas, todas definidas, todas significantes, todas ordenadas, dispuestas sistemáticamente a la luz de un lenguaje claro. Si este haz de relaciones se transmite con éxito y sobrevive se convierte en ciencia, la que hace el pasado comprensible, al presente progresivo y al futuro predecible.

Tan incontestable es el éxito de este lenguaje universal que, como suele ocurrir con el éxito, acaba por olvidar su origen: una mirada de asombro, una interrogación sin respuesta, un primerísimo diálogo entre lo mirado y quien lo mira. Así, forzando la amnesia, la ciencia impone interpretaciones, dirige las preguntas y señala la dirección correcta de las respuestas. Y lo hace porque el sujeto que conoce comparte con sus semejantes las mismas categorías. Si no, no sería posible que la cera fuera la misma cera después de haberse derretido, de haberse esfumado, de haber inaugurado, con Descartes, un método de conocimiento universalmente válido.

No es casualidad, o si lo es no lo parece, que la cera sea el material protagonista de esta exposición. Esta vez, sin embargo, no ilumina ningún método ni allana el camino de ningún descubrimiento. Esta vez, la cera oculta los hallazgos, revierte el proceso. El gesto del artista es claro: de vuelta a la sombra, los objetos catalogados se vuelven desconocidos, como los contornos que se difuminan detrás de una niebla. El gesto, insisto, es claro: devuelve el objeto a su origen sin nombre, al asombro y a la pregunta primera y, por lo tanto, a la posibilidad de un nuevo diálogo entre observador y objeto observado.

Sin la mediación de un sistema establecido de signos, conceptos y categorías, las posibilidades de interpretación se multiplican, una apertura hermenéutica que es más propia de la experiencia estética que de la razón disciplinada de las ciencias. El mérito se encuentra, aquí, enterrado: bajo capas nuevas, el objeto de conocimiento, descrito, catalogado, concreto y unívoco, deviene, por voluntad del artista, obra de arte, única, abierta y polisémica. Qué clase de conocimiento ofrece esta nueva obra-objeto dependerá de quien la contemple. Será un asunto privado, anónimo y, sin embargo, real.

Santiago Mazarrasa

Imagine an ordinary object—one you do not recognize, a material contained within a form that resists definition. Until you name it, that object is nothing; it barely exists. Now imagine another object, at a cautious distance from the first—another form, another matter, another mass. Until it too is named, no relationship exists between them. Who, among all the anonymous and silent observers, holds the prerogative to give a name to that which has none? Everyone and no one, since naming things is, paradoxically, an anonymous task. Every name, moreover, is the product of a historical process. The farther back it reaches, the less traceable it becomes—like a footprint slowly fading over time.

Now imagine that both objects exist, that they have been named, that an agreement has been reached to name them—an agreement conventional, collective, belonging to everyone and to no one—and that it endures unaltered through the seasons, through years, through ages and eras. Both objects, and the relationship they now share, finally possess a meaning that can be transmitted, refined, debated, and ultimately rejected. In short, knowledge finally exists: the object is no longer mute, no longer alone; it now coexists with a multitude of forms—each defined, each signifying, each systematically arranged under the light of a clear language. If this network of relations is successfully transmitted and endures, it becomes science—the science that renders the past comprehensible, the present progressive, and the future predictable.

So indisputable is the success of this universal language that, as so often happens with success, it eventually forgets its origin: a gaze of wonder, a question without answer, a primal dialogue between what is seen and the one who sees. By enforcing this amnesia, science imposes interpretations, directs the questions, and dictates the proper direction of the answers. It does so because the knowing subject shares with their peers the same categories; otherwise, it would be impossible for wax to remain wax after melting, vanishing, and inaugurating—through Descartes—a universally valid method of knowledge.

It is no coincidence—or if it is, it hardly seems so—that wax is the central material of this exhibition. This time, however, it illuminates no method, nor does it pave the way for any discovery. This time, wax conceals the findings; it reverses the process. The artist’s gesture is clear: returned to shadow, the catalogued objects become unknown once again, their contours blurring like shapes behind a mist. The gesture, I insist, is clear: it returns the object to its nameless origin, to wonder and to the first question—and thus to the possibility of a new dialogue between observer and observed.

Without the mediation of an established system of signs, concepts, and categories, the possibilities of interpretation multiply—an opening more proper to aesthetic experience than to the disciplined reason of the sciences. Here, the merit lies buried: beneath new layers, the object of knowledge—once described, catalogued, concrete, and univocal—becomes, by the artist’s will, a work of art: unique, open, and polysemic. What kind of knowledge this new art-object offers will depend on whoever contemplates it. It will be a private matter, anonymous and yet real.

Text by Santiago Mazarrasa

El “Mea Culpa” de Émile Cartailhac se expresó dos veces: primero, en el paradigmático artículo publicado en la revista L’Anthropologie de 1902, donde la retractación adoptó un tono exculpatorio; y después, en la intimidad doméstica, al calor de una mesa camilla en la casa de María Sanz de Sautuola, cuando quien había juzgado con dureza no pudo sostener la mirada a quien había sepultado a su padre bajo el estigma de la impostura y el descredito. Ambos episodios —el público y el íntimo— revelan no sólo una inflexión en la ética del cientificismo moderno, sino también la manera en que el discurso científico logra imponerse, incluso en sus rectificaciones, a través de las grietas de la razón.

La reivindicación póstuma de Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola frente al desprestigio con que la arqueología académica desacreditó su hallazgo constituye uno de los ejemplos más nítidos de cómo, ya en el siglo XX, los discursos éticos comenzaban a ser acogidos por los paradigmas racionales de las tecnologías de la historia. Una transición discursiva que no solo repara, sino que también legitima, a través de su propia transformación, los errores que antes sustentó.

Y es que, ante la historia, el discurso científico se presenta velado por su propia estructura: una tautología que se despliega desde la afirmación de un yo-comunitario; de un tiempo exento de cronología, de una voz que transita por distintas bocas abiertas, de una caligrafía insensible, traslúcida y sorda. Su aparente transparencia es, en realidad, una forma de opacidad: una sintaxis de autoridad y erotismo que se impone mientras se disimula.

En tanto que discurso, el pensamiento que se cierne sobre la historia responde a un régimen de deducción; a un margen de lectura e interpretación que convierte en evidencia aquello que ha sido imaginado como prueba. Sin embargo, los márgenes históricos que articulan la cronografía del hacer humano rara vez se presentan como legibles. Y por eso, rara vez, somos llamados a leer la historia.

De vez en cuando daremos con ella. Quienes puedan acceder a sus recovecos, al menos. Porque no neguemos que sus accesos —los de la historia— suelen quedar vedados para quienes no cuentan con la mediación de un testimonio próximo, iluminado, que otorgue luz para superar las barreras del umbral. Un testigo sígnico, portador de indicios, que habilite una lectura situada del tiempo; una antorcha de tuétano.

El pensamiento histórico, tal como lo hemos heredado del cientificismo ilustrado del siglo XVIII, no es sino un sistema de despliegue: un marco ordenado que pretende traducir la complejidad de lo vivido a través de operaciones de registro, archivo e interpretación. Pero esa pretensión de claridad es también un dispositivo que abre sentidos tanto como los clausura.

Así, en este sistema de ocultación y veladura, Manuel Minch despliega una serie de ejercicios sígnicos que emergen del terreno —histórico, estético y geográfico— de Altamira, para operar como una contraescritura de la historia. A partir de esta base geológica y simbólica, la obra introduce indicadores especulativos que cuestionan la disyunción entre el discurso científico y los procesos de metodologización histórica, evidenciando cómo la ciencia opera desde una red de dependencias discursivas, más que desde una objetividad autosuficiente.

Las piezas presentadas en esta exposición se articulan a través de una serie de intra-acciones entre testigos historiográficos y lecturas fenomenológicas, dando lugar a ejercicios materiales y visuales que cuestionan la configuración del pasado como una entidad fija y cerrada.

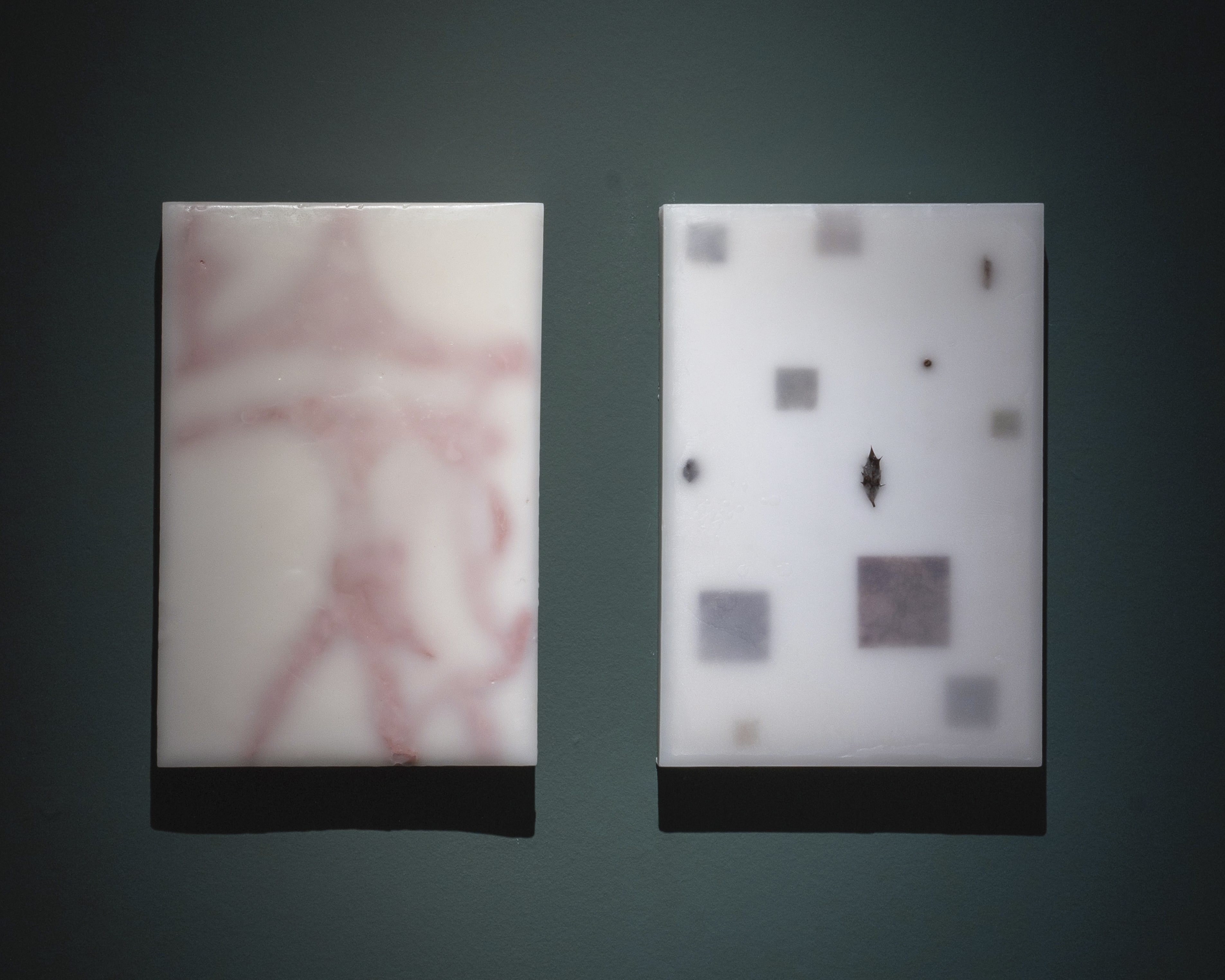

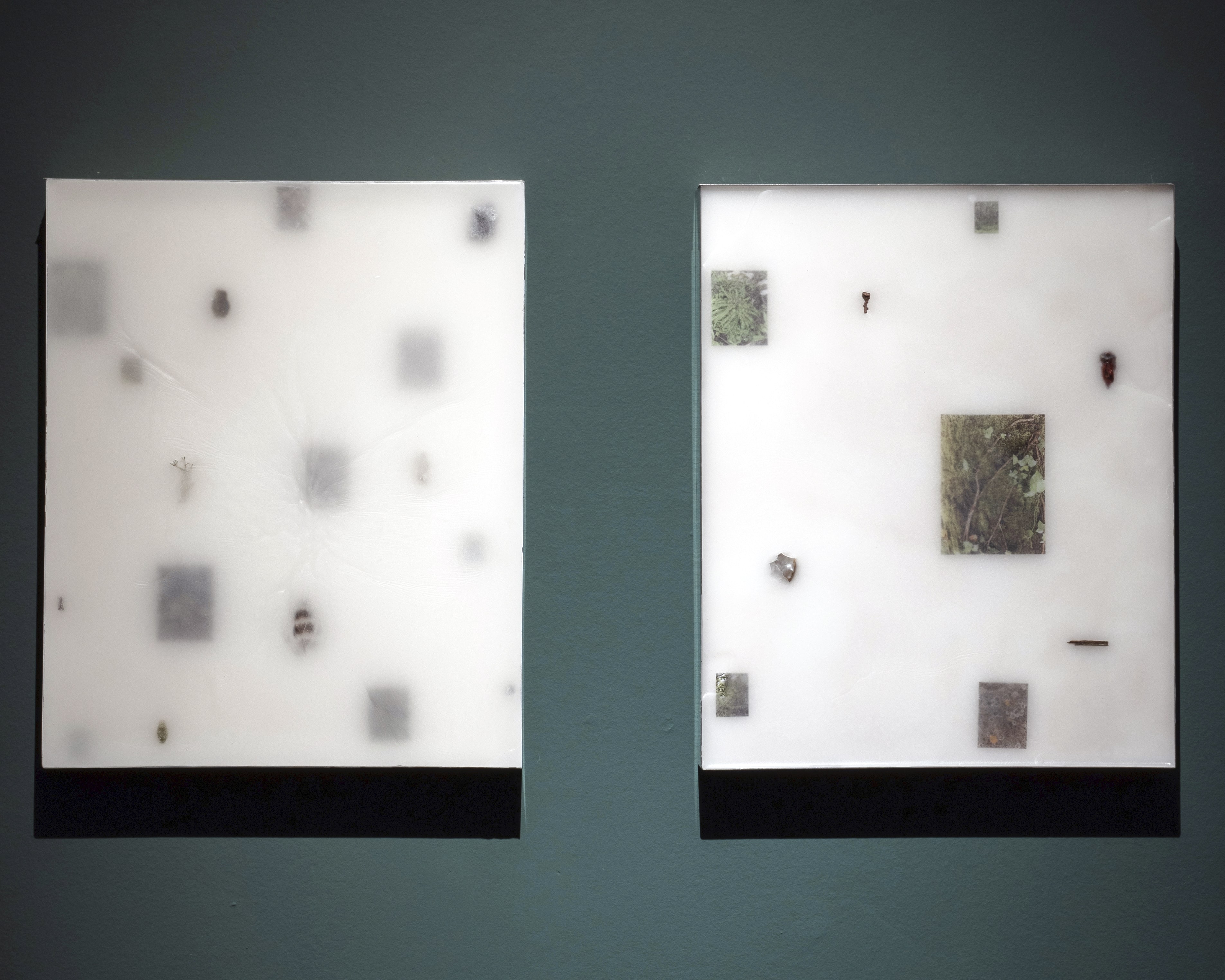

Partiendo de un principio de serialidad estructurante, propio de las lógicas clasificatorias que sustentaron la modernidad científica, el proyecto se inscribe en una genealogía de formas catalográficas que modelaron el pensamiento binomial ilustrado. Por ejemplo, la propuesta racimada que toma el nombre de Recolección (2025) actúa como un ecosistema visual y material donde convergen múltiples referencias dispuestas según una lógica filogenética: no por jerarquía, sino por vecindad, por mutua implicación y divergencia histórica. Las veladuras de cera que cubren la superficie del lienzo bajo la que se dispone ese ecosistema, operan como membranas semiopacas que desplazan cualquier lectura unívoca, reconfigurando las relaciones significantes hacia una agencialidad latente, en la que lo visible queda tensionado por lo archivado y lo potencial.

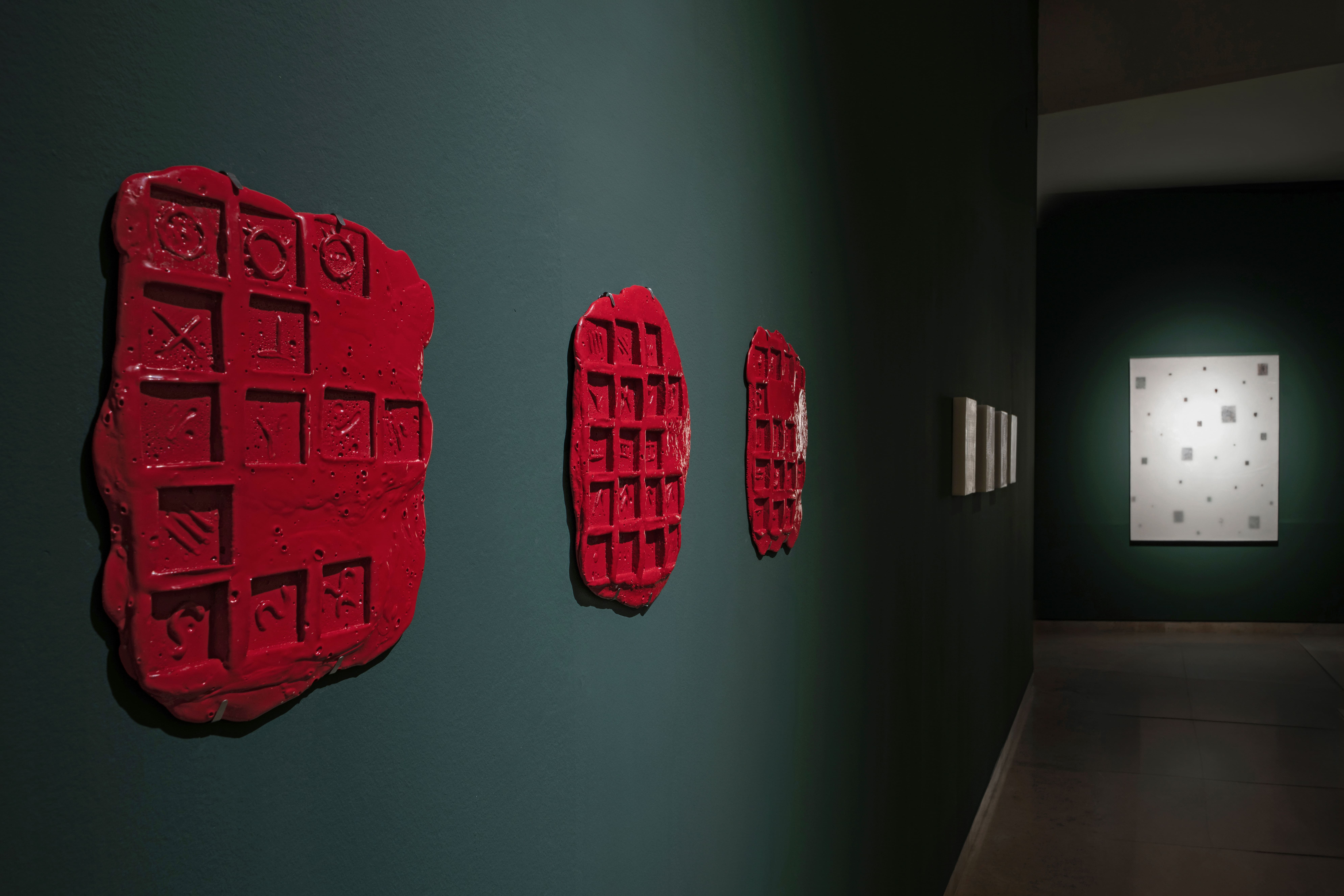

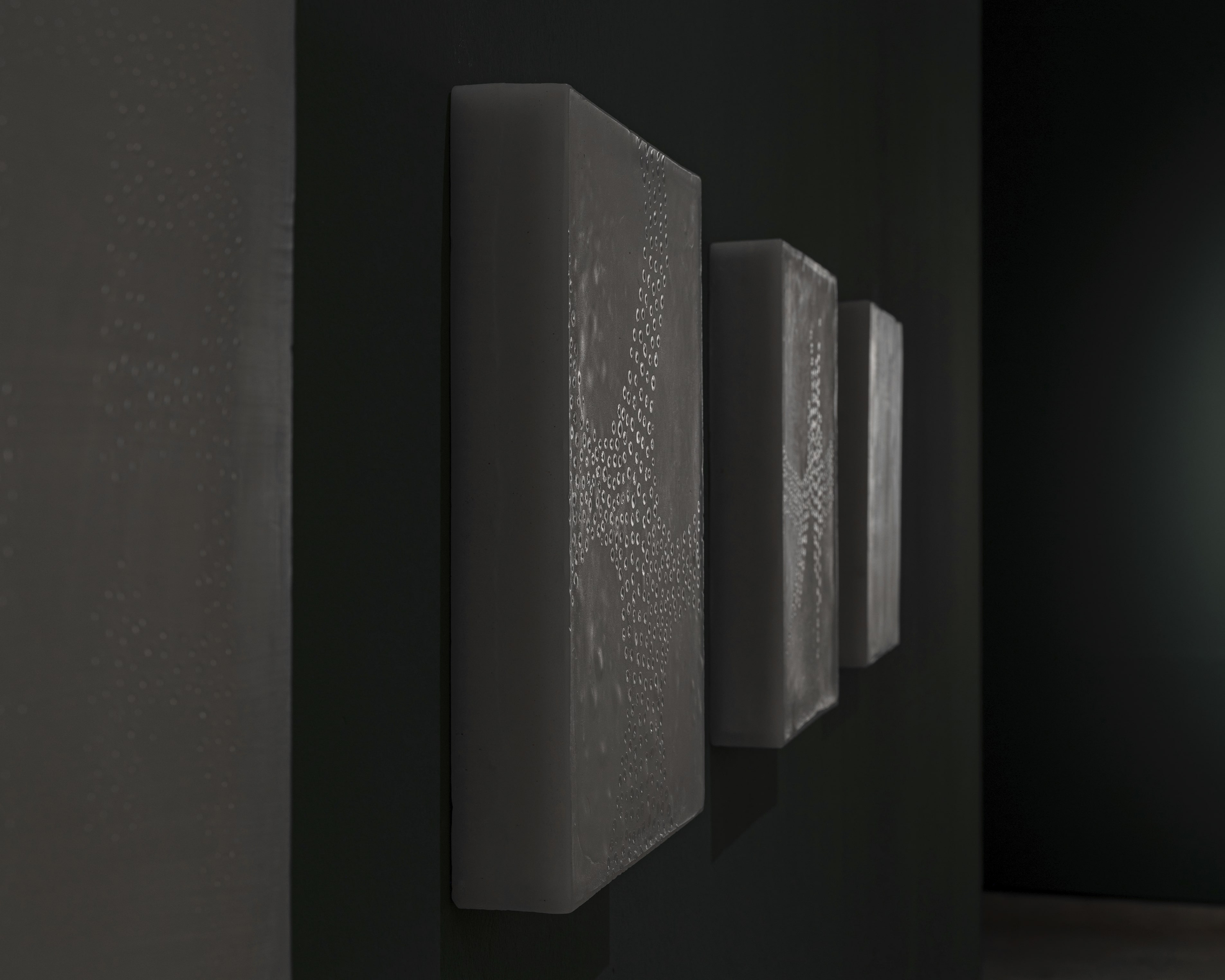

Asimismo, otras series que conforman el proyecto —como los ejercicios de escritura Puntiformes (2025) o las composiciones matéricas en lacre rojo de Sellos (2025)— operan desde una apropiación crítica de las metodologías propias del análisis morfológico, aquellas que históricamente buscaron reconstruir el pasado a partir de la observación estructurada de formas persistentes, rastros fósiles o huellas gráficas. Estos lenguajes, originados en sistemas científicos orientados hacia una verdad empírica y objetiva, son aquí reconfigurados desde una lógica especulativa que cuestiona sus propias premisas de origen.

En definitiva, lejos de reproducir la autoridad de los sistemas, Manuel Minch propone un desplazamiento: en lugar de consolidar significados estables, los modelos discursivos que componen esta exposición activan una latencia semiótica, donde la forma y la inscripción actúan como campos abiertos y miradas exorbitadas.

Desde la perspectiva de los sistemas lingüísticos y de representación que el artista activa, se despliegan formas en las que los modelos discursivos de las ciencias no solo interpretan el mundo, sino que producen potencias agenciales que configuran lo real. Tal vez por eso Cartailhac, en su gesto tardío de arrepentimiento, exclamara: «¡En vano recurrimos a la imaginación, en vano a la etnografía!» —como si intuyera que toda objetividad no es más que una ficción situada, una construcción que habla tanto de quien enuncia como de aquello que pretende explicar.

Texto por Álvaro Porras

The “Mea Culpa” of Émile Cartailhac was expressed twice: first, in the paradigmatic article published in the journal L’Anthropologie in 1902, where his retraction adopted an exculpatory tone; and later, in the intimacy of a domestic setting—around a small table in the home of María Sanz de Sautuola—when the man who had judged so harshly could no longer sustain the gaze of the woman whose father he had buried under the stigma of imposture and disgrace. Both episodes—the public and the private—reveal not only a turning point in the ethics of modern scientism but also the way in which scientific discourse manages to assert itself, even in its rectifications, through the fissures of reason.

The posthumous vindication of Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola against the discredit cast upon his discovery by academic archaeology stands as one of the clearest examples of how, already in the twentieth century, ethical discourses began to be absorbed into the rational paradigms of the technologies of history. A discursive transition that not only repairs but also legitimizes—through its own transformation—the very errors it once sustained.

Before history, scientific discourse appears veiled by its own structure: a tautology unfolding from the affirmation of a communal self; of a time exempt from chronology; of a voice that passes through multiple open mouths; of a handwriting both insensitive, translucent, and deaf. Its apparent transparency is, in truth, a form of opacity: a syntax of authority and eroticism that imposes itself even as it conceals its own power.

As discourse, the thought that hovers over history responds to a regime of deduction—to a margin of reading and interpretation that turns into evidence what has been imagined as proof. Yet the historical margins that articulate the chronography of human activity rarely appear as legible. And thus, rarely are we truly called to read history.

From time to time, we may stumble upon it—those of us able to access its recesses, at least. For we cannot deny that the thresholds of history are often barred to those who lack the mediation of a nearby, illuminated testimony capable of casting light beyond the barriers of the threshold. A semiotic witness, bearer of traces, enabling a situated reading of time—a marrow torch.

Historical thought, as we have inherited it from the Enlightenment’s scientistic legacy of the eighteenth century, is nothing more than a system of unfolding: an ordered framework that seeks to translate the complexity of lived experience through operations of recording, archiving, and interpretation. Yet that very claim to clarity is also a device that opens meanings even as it closes them.

Thus, within this system of concealment and veiling, Manuel Minch unfolds a series of semiotic exercises that emerge from the historical, aesthetic, and geographical terrain of Altamira, operating as a counter-writing of history. From this geological and symbolic foundation, the work introduces speculative indicators that question the disjunction between scientific discourse and the processes of historical methodologization, exposing how science operates from within a network of discursive dependencies rather than from any self-sufficient objectivity.

The pieces presented in this exhibition are articulated through a series of intra-actions between historiographic witnesses and phenomenological readings, giving rise to material and visual exercises that question the configuration of the past as a fixed and closed entity.

Starting from a principle of structuring seriality—typical of the classificatory logics that sustained scientific modernity—the project inscribes itself within a genealogy of catalographic forms that shaped Enlightenment binomial thought. For example, the clustered proposal titled Recolección (2025) functions as a visual and material ecosystem where multiple references converge according to a phylogenetic logic—not through hierarchy, but through proximity, mutual implication, and historical divergence. The wax veils covering the surface of the canvas beneath which this ecosystem is arranged act as semi-opaque membranes that displace any univocal reading, reconfiguring the network of meanings toward a latent agency, in which the visible is held in tension by what is archived and potential.

Likewise, other series that comprise the project—such as the writing exercises Puntiformes (2025) or the material compositions in red sealing wax titled Sellos (2025)—operate through a critical appropriation of the methodologies proper to morphological analysis, those that historically sought to reconstruct the past through the structured observation of persistent forms, fossil traces, or graphic imprints. These languages, originating in scientific systems oriented toward empirical and objective truth, are here reconfigured through a speculative logic that questions their own foundational premises.

Ultimately, far from reproducing the authority of systems, Manuel Minch proposes a displacement: rather than consolidating stable meanings, the discursive models composing this exhibition activate a semiotic latency, where form and inscription act as open fields and expanded gazes.

From the perspective of the linguistic and representational systems the artist activates, forms unfold in which the discursive models of science not only interpret the world but also produce agential potentials that shape reality itself. Perhaps that is why Cartailhac, in his belated gesture of repentance, exclaimed: “In vain we appeal to imagination, in vain to ethnography!”—as if sensing that all objectivity is nothing but a situated fiction, a construction that speaks as much of the one who enunciates as of that which he seeks to explain.

Text by Álvaro Porras